History of the Van Allen House

DEVELOPMENTAL HISTORY

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

2.1 Historical Overview

Introduction

This history of Oakland is not meant to be all-inclusive, but to look at the historical trends of the region and how Oakland developed based on the surrounding influences. This information will how that the Van Allen House property, located at 1-3 Franklin Avenue, was a product of its time and place.

2.1.1 History of Oakland, New Jersey

Early Oakland was a secluded wilderness settled by the Minsi Indians, a tribe of the Lenni Lenapes. The land came into the hands of colonial settlers by the end of the seventeenth century. By this period, what was known as East Jersey had been purchased by twenty-four proprietors from the estate of George Carteret. The proprietors agreed to sell portions of this land if the Indian tribes who lived there were also involved in negotiations.

Early deeds between the Indian tribes, the proprietors and colonial settlers were often vague in boundary descriptions. As such, it is difficult to determine the first colonial settlers of present-day Oakland. It is believed, though, that portions of the Borough were included in the Schuyler and Brockholst purchase of 1695, the Ryerson and Westervelt purchase of 1709, and the Willocks and Johnson Patent from sometime in the early-eighteenth century.4 Arent Schuyler is known as the first colonial landholder in the area. On June 5, 1695, he signed a deed for the purchase of approximately 5,500 acres for himself and several associates in the Pompton Valley. 5 The patent for this land was signed by the proprietors on November 1, 1695.6.

Dutch settlers began to arrive in the area, at this time called “The Ponds” or “Yaupough” (Yawpo)

around 1700.7. According the J.M. Van Valen’s History of Bergen County, there was a small pond of water in the area, with a grist mill standing near a church.8 It is said that early settlers called the area around the church, “De Panne,” which is interpreted to mean “The Ponds.”9 By 1710, when this church was founded, there were approximately ten families in the Ponds,10 or the southern section of Oakland. The area including Oakland also became part of Bergen County in that year.11

Some of the earliest settlers in the area included Yan Romain, who purchased 600 acres from the Willcox and Johnson Patent in 1724,12 the Schuylers in 1730, the Garretsons as early as 1760,13 and the Van Allens (Van Alen), who purchased 600 acres on the Ponds Flats about the same time.14 Other early families included the Ackermans, Bogerts, Ryersons, Van Houtens, Van Winkles and Westervelts.15 The area grew slowly through the middle years of the eighteenth century, and in 1771, the Ponds became part

4 Ryerson Vervaet, Valley of Homes: The Ponds, Yaupough, Oakland, 1695-1952 (1952), 9-10.

5 Shirley Iten Kern, The Years Between: A Pictorial History of Oakland (1964), 1.

6 Vervaet, 11.

7 From early Colonial times the northern or Valley portions of the Borough were referred to as Yawpo or Yaupough

after the Minsi Indian chief Iauapagh who once ruled this land. The southern section of Oakland, The Ponds, was derived from the Dutch “De Panne” and was probably a descriptive name for the many small ponds in the area of Oakland and Franklin Lakes (cited in Kern, The Years Between:

A Pictorial History of Oakland).

8 James M. Van Valen, History of Bergen County, New Jersey (New Jersey Publishing and Engraving Company, 1900), p. 185.

9 Vervaet, 13.

10 Vervaet, 11.

11 The First Years.

12 Vervaet, 12.

13 Van Valen, 185.

14 Frances Westervelt, History of Bergen County New Jersey, 1630-1923 (New York, 1923), 280.

15 Vervaet, 12, and Westervelt, 280.

HISTORIC PRESERVATION PLAN

VAN ALLEN HOUSE PROPERTY

OAKLAND, BERGEN COUNTY, NEW JERSEY

2. DEVELOPMENTAL HISTORY

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

13

CONNOLLY & HICKEY HISTORICAL ARCHITECTS, LLC

of Franklin Township when it was established June 1, 1771. By the start of the American Revolution, The Ponds had grown to include about 100 residents.16 Oakland’s roads were vital supply lines for the Continental Army during the American Revolution.

Ramapo Valley Road (Route 202) was an important route to West Point. While no major Revolutionary events or battles took place within the Borough’s present boundaries, George Washington relied heavily on this route to funnel information and supplies, and troops continually passed through the area’s valley trails throughout the War.

In Ryerson Vervaet’s The Valley of Homes, the author states that maps of the area (Figure 4) drawn by Robert Erskine, cartographer of the Continental Army, showed the Ponds Church, two gristmills at the intersection at Ramapo Valley Road and Franklin Avenue including the house of Henry Van Alen (Van Allen), as well as other houses including those belonging to Abraham Schuyler and Garret Garetson.17

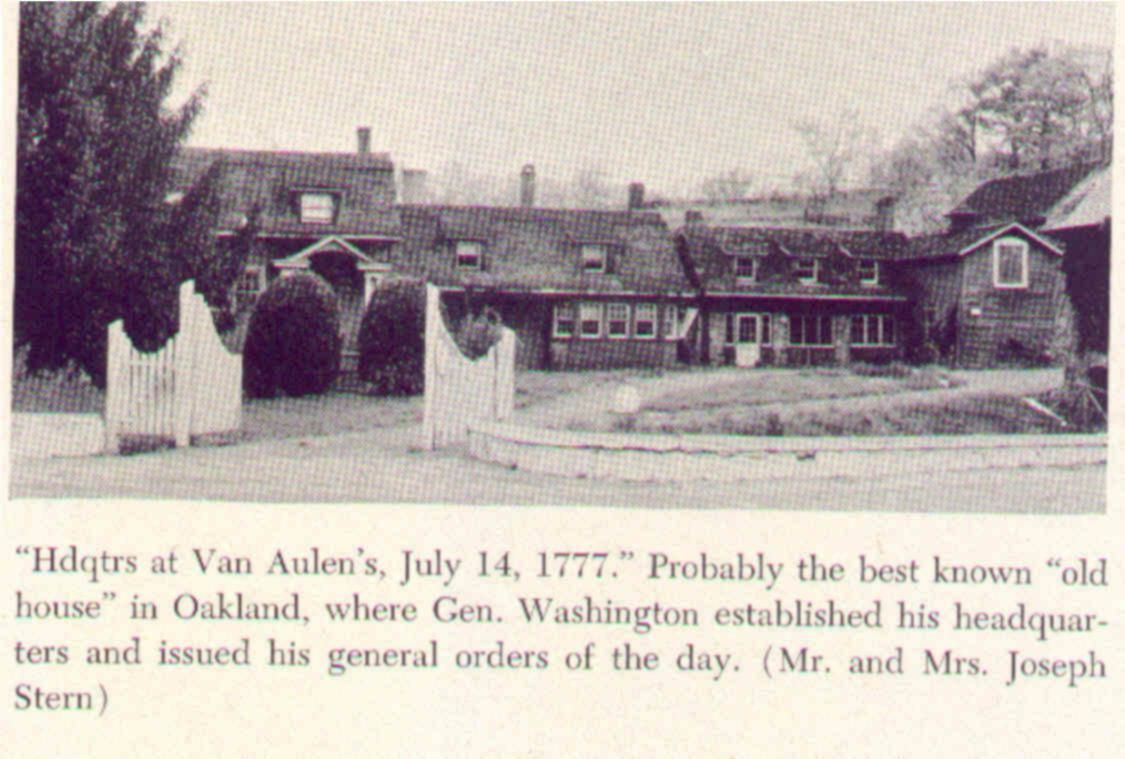

The Henry Van Alen house would act as Washington’s temporary headquarters on July 14, 1777.

On that morning, Washington left his headquarters house in Pompton Plains. The army began their

march north but because of inclement weather and nearly impassable roads, the General halted the

march. Here a communication to Major Philip Schuyler was written in which General Washington stated that he learned of the escape of a part of the northern army under Schuyler’s command and of the loss of Ft. Ticonderoga to General Burgoyne’s British Army. In his letter to the Continental Congress, dated July 14, 1777 (Figure 5), George Washington stated, Vanaulens, 8 miles from Pompton Plains, July 14, 1777.

“Sir I arrived here this afternoon with the Army, after a very fatiguing March, owing to the Roads which have become extremely deep and miry from the late Rains. I intend to proceed in the Morning toward the North (Ed.: Hudson) River, if the Weather permits. At present it is cloudy and heavy and there is an Appearance of more Rain. By the Express, who will deliver this, I just now rec’d a Letter from Genl Schuyler, advising me for the first time, that General St. Clair is not in the Hands of the Enemy.”

General Washington ordered that the army continue its trek north upon clearing of the weather on July 15, 1777, and he and his army marched north into the Ramapo Pass in New York State at Suffern’s Tavern. In 1780, the British burned the jail and courthouse in Hackensack, and Oakland temporarily became the County seat. Oakland served as the County seat of Bergen for nearly three years. Despite this designation, the area changed little over the remaining years of the eighteenth century into the nineteenth century. While gristmills, woodcutters and charcoal makers began to prosper over the period, farming still sustained most families. 18 Many of the old Indian trails had become adequate to support wagons and farmers were able to sell produce in Paterson, Newark and New York.

Farming remained the dominant occupation of the area’s Dutch settlers until after the Civil War, when advancements in transportation began to transform the countryside. (Figure 7) In 1869, the New Jersey Midland Railroad reached the Ponds. The opening of the railroad also brought about the renaming of the area to “Oakland.” At the time the railroad was completed, citizens met to choose a new name, and

16 Vervaet, 11.

17 Vervaet, 31-32.

18 Kern, 12.

HISTORIC PRESERVATION PLAN

VAN ALLEN HOUSE PROPERTY

OAKLAND, BERGEN COUNTY, NEW JERSEY

2. DEVELOPMENTAL HISTORY

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

14

CONNOLLY & HICKEY HISTORICAL ARCHITECTS, LLC

David C. Bush suggested Oakland.19 In 1871, a railroad depot was built,20 and a post office was

established in 1872.21 While the ability to transport farm and dairy products by rail at first offered new opportunities for farmers, transportation also opened up the area to industry and development, which slowly transformed the traditional agricultural character. Better transportation provided greater opportunity for the transportation of products out of Oakland, and in turn, introduced vacationers to this still well-preserved countryside. (Figure 8)

In the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, the Ramapo River and Oakland’s various springs and streams provided waterpower necessary for industry. Mills in the area in this period included a cider mill and sawmill on the Ramapo River owned by Abram Garrison and a gristmill and sawmill at the Long Hill Brook owned by Samuel P. Demarest.22 In 1890, the American E.C. Powder Company factory was established in Oakland, and in 1894 the Wilkens brush factory opened, producing bristles for brushes. In the same period, Oakland became well known as a resort area. It is said that during “Oakland’s resort boom days, there were at least seven public beach resorts and many more hotels.”23 These hotels

included the Calderwood Hotel, the Oakland Inn, the Brooksyde Inn and the Hafel Hotel. The

recreational use of the Ramapo River became particularly popular after 1900. In addition to wealthier vacationers, Oakland’s numerous bodies of water attracted local and regional industrial workers.

With the rise in industry and popularity among vacationers came an increase in population and building construction. Most settlement remained concentrated along Ramapo Valley Road. While farmland remained, numerous mansions and country homes began to appear within the landscape. In writing the

History of Bergen County, New Jersey in 1900, J.M. Van Valen noted that “The village has a reputation worthy

of an enterprising people, and with its railroad, hotel and stores, and two prominent manufacturing

enterprises, it is on the progressive.”24 By the time the area was incorporated as the Borough of Oakland (formed from Franklin Township) in 1902, it had a population of approximately 500 (Figure 9). The population grew to 568 in 1910 and to 628 in 1915.25 (Figures 10 and 11)

Industry slowly died in the area in the 1920s as electricity, which had arrived in Oakland in 1916, made the use of waterpower obsolete. The gunpowder factory closed in 1920, 26 and by 1923, only two industries were still in operation, the Kanouse Oakland Spring Water Company (which bottled water) and the Wilkens brush factory.27 The brush factory closed in 1928, and almost all industry ceased in Oakland by the end of the decade.28 Due to the closing of the mills and other manufacturing plants, Oakland witnessed its first decline in population. By 1920, the population had dropped to 497 residents.29

While Oakland continued to attract resort visitors, both industry and farming nearly disappeared in the mid-twentieth century. Between the 1920s and the 1940s, the population remained nearly static due to the Great Depression and World War II (Figure 12). Tracts of land were sold to developers beginning in the late 1930s for residential development, but suburban development did not begin to accelerate until 19 Van Valen, 185-186.

20 John Madden and Kevin Heffernan, Images of America: Oakland (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2003), 91.

21 Vervaet, 86.

22 Vervaet, 45.

23 Madden, 95.

24 Van Valen, 185.

25 Westervelt, 391.

26 Madden, 48 and 49.

27 Westervelt, 391.

28 Madden, 48 and 49.

29 Westervelt. 391.

HISTORIC PRESERVATION PLAN

VAN ALLEN HOUSE PROPERTY

OAKLAND, BERGEN COUNTY, NEW JERSEY

2. DEVELOPMENTAL HISTORY

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

15

CONNOLLY & HICKEY HISTORICAL ARCHITECTS, LLC

after World War II so that by 1950 there were 1,5817 residents in Oakland.30 The post-World War II period of residential construction resulted in the fifth highest population increase in New Jersey within a population of over 9,000 residents by 1960. 31 With the construction of County Route 208 to Oakland in 1962, highway access officially established the Borough as a residential commuting community. By 1964, Oakland had 13,000 residents.32 Oakland has remained a suburban community since this time, with over 12,000 residents. Traces of its agricultural and industrial past can still be seen in the early structures that remain along the Borough’s earliest thoroughfares and along the Ramapo River.

2.1.2 The Van Allen House

In the spring of 1748, Hendrick Van Allen and his family moved to the intersection of what is now

Ramapo Valley Road and Franklin Avenue on a 200-acre grant from the English Crown. As discussed in Section 2.1 History of Oakland, New Jersey, the Van Allen house is shown at this intersection on a map drawn by Robert Erskine in 1779. Built as a Dutch-American farmhouse, the house began as a four-room farmhouse growing through additions to its east over time. The building reflects many of the elements of architecture used by the Dutch-American cultural group in the mid-eighteenth century at both its original building and the later additions made in the mid-to-late-eighteenth century.

As noted in Section 2.1 History of Oakland, New Jersey, the Van Allen (or Van Alen) family were early settlers in this region. The first known Van Alen in the area was Pieter Gerritse Van Alen who emigrated from Rotterdam and settled along the Saddle River. Pieter was married on August 11, 1706 in Hackensack to Trintje Hopper. Pieter and Trintje had twelve children, including eldest son Hendrick, baptized at Hackensack on June 2, 1707. Hendrick married Elizabeth Doremus (b. February 3, 1717), and they had ten children. Some of these children were baptized between 1739 and 1748 in Pompton Plains Church, where Hendrick had become a member in 1738. Rosalie Fellows Bailey speculates in Pre-RevolutionaryDutch Houses and Families in Northern New Jersey and Southern New York that Hendrick likely first settled in the Pompton Plains area, and then moved to “the Ponds” community in 1748, the year in which he became deacon at the Ponds Church, which was located one mile west of his home in Oakland.33

By the time of the American Revolution, Erskine’s map shows that in addition to his home built at the intersection of present-day Ramapo Valley Road and Franklin Avenue, Hendrick had also established a grist mill across the road from his house. It appears that the Van Allen house played a central role in its community, and as previously noted it served as the temporary headquarters of George Washington on July 14-15, 1777. Van Allen and his fellow church members, who were of Dutch descent, had no loyalty to England and supported General Washington and the Continental Army. The Van Allen House occupied a strategic position in Oakland’s landscape. The Valley Road (now Route 202) served as a major supply artery between the north and south and was protected by the natural landscape between the mountains and the river. On July 14, 1777, Washington and his troops were headed for Sussex and General Washington called a halt to the march due to the inclement weather and nearly impassable road conditions. Washington stationed his troops outside the Van Allen home. During his stay at the Van Allen home, Washington wrote three separate correspondences which can be found in the Library of

30 Kern, 24.

31 Kern, 24.

32 Kern, 24.

33 Terry Karschner. “Van Allen House.” Oakland, Bergen County, New Jersey. National Register #73001080, Section 8,

1973.

HISTORIC PRESERVATION PLAN

VAN ALLEN HOUSE PROPERTY

OAKLAND, BERGEN COUNTY, NEW JERSEY

2. DEVELOPMENTAL HISTORY

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

16

CONNOLLY & HICKEY HISTORICAL ARCHITECTS, LLC

Congress.34 One letter to his troops ordered that the troops recommence their march toward Sussex upon clearing of the weather on July 15, 1777. Hendrick Van Allen occupied his home with his wife and children from 1748 until his death in July 1783. He remarried January 20, 1761 to Thomasina Earle after his first wife died. 35 His will, written in 1778, mentions his wife, Thomasina, his eldest son Peter, his sons William, Gerret and John, and his deceased son Dr. Andrew Van Allen. The will states that Peter and William had already received their portions of the estate.36 Hendrick had directed that his property be sold and the purchase money divided among his children, including Elizabeth Maria, then wife of Cornelius Vanderhoof. On August 2, 1783, the property was deeded to Cornelius Vanderhoof, “All that messuage Tennant and House, Barn, Mill, etc.”

sold for eight hundred and sixty pounds.37 Another indenture was also recorded on August 2, 1783 (Book D, page 224). The Indenture is a deed from the heirs of Hendrick Van Allen whereby they released the land to Vanderhoof. It states:“Indenture between John H. Van Alen, Garret Van Alen, Hessel Van Alen, heirs of their brother, Dr. Andrew Van Alen of the first part to Cornelius Vanderhoof of the second part. Whereas Hendrick Van Alen late, etc. did by his Last Will and Testament order that six weeks after his decease his real estate to wit his plantation with all the appurtenances thereunto belonging and houses, etc. be disposed of at a Publick Sale by the Executors of his last will and the purchase money to be divided among John H. Van

Alen, Garret Van Alen, Hessel Van Alen, Elizabeth Maria, the wife of the said Cornelius Vanderhoof and the heirs of the said Doctor Andrew Van Alen, etc.”

Cornelius Vanderhoof is buried at the cemetery of the Ponds Church, with the date of death March 8, 1788. Vanderhoof left a will, dated January 19, 1788. His executors were listed as James J. Bogert, Peter Ward and Giles Mead. The abstract of his will states: “Vanderhoof, Cornelius, of Franklin Township, Bergen County, Will of Wife Elizabeth all real and personal estate while my widow./ My uncle Hessel Van Allen, is to have a good support out of my estate./ My wife is to have the furniture she owned before we were married. Daughter Ann 4 pounds/ Daughter Anne, Rachel, Elizabeth and Jaine to have the whole estate after my wife’s death, except the Dutch Bible which Rachel is to have./ Executors: Giles Mead, James S. Bogert and Peter Ward./ Witnesses: Abraham Manning, Uzel Meeker, Harmanus Van Huysen./ Proved April 21, 1788.”38

Documentation details regarding ownership of the house between 1788 and 1864 are illegible. In 1864, Henry Demarest transferred the deed to the property to Martin Van Houten, aged 42 who was a farmer. According to the 1870 U.S. Census, Van Houten was living with his mother, Hester Van Houten, age 65. In residence was also Jno Van Houten, 16, a farm laborer, and York Benson, age 9. The relationship to Jno is unclear.39 The Van Houten’s immediate neighbors in the 1870 Census were the Bensons. Anthony Benson, who was the head of household, was listed as a farm laborer and owned no real estate or personal property. It is possible given the proximity of the two households and that one Benson child 34 The Morning ___, November 30, 1973, 21.

35 Kathryn DuBois, Old Mills of Bergen County, Histories and Family Records, 1677-1954 (Bergen County Historical Society,

1954), no page numbers.

36 Hendrick’s executors were John Van Allen and Hassel Doremus.

37 Dubois, citing Book D, of Deeds, 1783, 221.

38 DuBois, citing New Jersey Archives, Calendar of Wills for 1786-90, 237.

39 Based on the 1850 and 1860 U.S. Federal Census, and the 1910 U.S. Federal Census records, it appears Martin Van

Houten married late in life and was not married when living at the Van Allen House. (Source: 1850, 1860 and 1910 U.S.

Federal Census. Available from www.ancestry.com. Accessed: June 21, 2011.)

HISTORIC PRESERVATION PLAN

VAN ALLEN HOUSE PROPERTY

OAKLAND, BERGEN COUNTY, NEW JERSEY

2. DEVELOPMENTAL HISTORY

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

17

CONNOLLY & HICKEY HISTORICAL ARCHITECTS, LLC

resided with the Van Houtens, the Bensons may have been tenants of the Van Allen property. Based on the 1860 and 1880 Federal Census Records, Martin Van Houten was a long-time resident of Oakland and according to the 1850 U.S. Federal Census was originally from Saddle River. In 1872, title for the property was conveyed to Aaron Garrison (Figure 8). According to the 1880 U.S. Federal Census, Aaron Garrison was living at the property with his wife, Mary. Both were 60 years of age and Aaron was listed as a farmer. However, according to the records, there was another family living on the property. Jeremiah Sanders, who was 40 years old and a laborer, was living with his wife Agnes and daughter, Anna, age 15.

According to the 1870 U.S. Federal Census, the Garrisons were living a short distance from the Van Houtens and owned real estate at the time. By 1885, the Garrisons conveyed the property to William Muller. According to the 1900 U.S. Federal Census, Muller lived in New York City with his mother-inlaw (head of household), wife, Kate Muller, his five children and his own mother. By 1910, he was listed as a farmer living in Oakland with his wife and three daughters. However, according to the title research, in 1900 Muller transferred the title to the Van Allen property to Edward Page, a successful merchant and businessman (Figure 9).

Edward Day Page (Figure 13) was born in Haverhill, Essex County, Massachusetts in 1856, but by 1860 was living in South Orange, New Jersey with his family. His father is listed as a merchant in the 1860 U.S. Federal Census. At the time Page moved to Oakland, he was a partner at the wholesale dry goods firm Faulkner Page & Co., located in New York. The firm Faulkner, Kimball & Co. was first established in Boston Massachusetts as a dry goods merchant and expanded to New York when Henry Page, Edward Page’s father and the nephew of one of the partners, M. Day Kimball, joined the firm and opened a branch office. At that point, the business grew and after the death of Kimball, the name was changed to Faulkner, Page & Co. Edward Page was educated at the Sheffield Science School at Yale University and joined Faulkner Kimball & Co. in 1875 as an office boy and became a full member of the firm in 1884, eventually becoming a senior partner. The business continued operations until December 1911 when it closed due to the wishes of the senior partners, including Edward Page.40 Page first came to Oakland in the late 1800s constructing a summer residence for his family. Page eventually moved to Oakland full-time to pursue farming. He purchased the Van Allen property along with 700 acres of land in Oakland in 1900, creating the Vygeberg Estate, for himself and his family. The Estate was a working farm (Figure 16) that encompassed almost all of the Mountain Lakes section of Oakland.41 The farm was primarily a dairy farm with several cow barns. In addition to dairy farming, oral history notes that he produced a variety of vegetables and eggs.42

As part of the estate, Page constructed a family mansion, known as De Tweelingen, (Figures 14 and 15) barns and other necessary buildings, including the Vygeberg Office (Stream House), which was built in 1902 on the Van Allen House property (Figure 19). The Vygeberg estate was featured in a book on the use of hollow-tile construction in residential architecture. The book specifically mentions that Page used an extensive amount of concrete possibly combined with hollow clay tile in the construction of additions to his main residence and an open pavilion. The main house appears to have been designed by New York-based architects, Rossiter and Wright circa 1890, and the author of the book, Frederick Squires was the architect for some of the additions and alterations made to the main house in the early-twentieth century, which were highlighted in Squires’ book.43

At the Vygeberg Office (Stream House), Page used a

40 “Old Dry Good Firm to Quit: Faulkner Page & Co., in Business 78 Years, to End with the Year”, The New York

Times, October 1911.

41 Madden, 35.

42 Oral history comments made by Al Potash, former Mayor of Oakland and one-time resident of the Van Allen House.

43 Frederick Squires, A.B.B.S, The Hollow-Tile House (New York: William T. Comstock, Co., 1913), 131, 156 and 157.

HISTORIC PRESERVATION PLAN

VAN ALLEN HOUSE PROPERTY

OAKLAND, BERGEN COUNTY, NEW JERSEY

2. DEVELOPMENTAL HISTORY

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

18

CONNOLLY & HICKEY HISTORICAL ARCHITECTS, LLC

new type of stucco technique that appears to have reduced installation time as the substrate was readily nailed to the framing and only a thin layer of stucco rather than a three-coat system was needed over the substrate. For more information about the stucco, see Section 2.2.4 Architectural Description.

The basement and first floor of the Vygeberg Office (Stream House) were used for dairy storage and

farm operations while the second floor served as residences. The Van Allen House itself also became part of the Vygeberg Estate (Figure 17) as the home of the farm manager, Alexander Ross, his wife and two children. It appears that the house also served as the dining hall for the farm workers. Page also constructed several other buildings adjacent to and east of the Van Allen House during his operations of the farm, none of which are fully extant today. One building served as an ice house where the other appeared to have a more residential or commercial use rather than a farm use (Figures 17 and 20). As often done with real estate, Page sold the property to his company, the Vygeberg Company in 1909, but then the deed was returned to Page by the Company in 1917.

Throughout operation of the Vygeberg Estate, Page was active in other businesses, hobbies and

associations. After Faulkner, Page & Co. closed, he became a special partner of Holbrook, Corey & Co., a commercial paper firm. He also headed a lecture series at the Sheffield School on the morals of business and penned a number of articles including “Morals in Modern Business” and “Trade Morals”.44

He was particularly interested in the publishing business, and owned and edited The Essex Register (NJ) as a hobby. He was president of the South Orange & Maplewood Traction Company, treasure for the Montrose Realty & Improvement Co., director of the Yale & Towne Manufacturing Co., and director of the First National Bank of Pompton Lakes. He also served several elected position in Oakland including councilman from 1902 to 1908, mayor from 1910 – 1911, recorder in 1912 and as vice president of the Board of Education in 1913. He belonged to a number of scientific, and cultural and arts committees and societies. In his private life, he was married to Cornelia Lee (also known as Nina) and had three children, Leigh, Allen Starr and Phyllis.45 Page’s first wife, Nina Page, died in 1915 and his son, Allan Starr, died in 1917. Page remarried, Mary Hall of Newton, NJ, in early 1918. Edward Page died of heart failure at his home in Oakland on December 25, 1918 at the age of 62.46

After Edward Page’s death, the Van Allen House property changed hands a number of times through the middle of the twentieth century and appears to have been a rental property for most of that period. In 1923, it was sold to a Catholic Seminary. According to deed documents, Mary Hall Page, Leigh Page and Phyllis Page McCorkley, executrices of the Page property conveyed the title to Peter J. O’Callaghan, the Father-in-Charge on June 15, 1923. In 1931, Edward M. Waldron Company, Incorporated acquired the title by sheriff’s sale. Waldron conveyed the title to the Friar Tuck Club in 1932. The Friar Tuck Club then returned the title to Waldron approximately seven months later (Figure 32). The property was then conveyed to the National House and Farm Association in 1936. The National House and Farms Association conveyed the title to Mae Stern and her husband, Joseph Stern in 1950.

In 1957, the deed was transferred to Knoll Top Construction which apparently bought it to demolish the buildings and develop the site into a gas station. The Borough of Oakland purchased the Van Allen House in 1966. According to hand written notes in the archives of the Historical Society of Oakland, between 1935 and 1938, the house was occupied by Robert and Dorothy (nee Johnson) Van Allen with their three children, Robert, Richard and Edward (Figure 25). Between 1938 and 1944, Mr. and Mrs. Alexander Potash lived

44 “E. Day Page Dies at Dinner Table”, The New York Times, December 26, 1918.

45 Who’s Who in Finance and Banking: A Biographical Dictionary of Contemporaries, 192-1922. Edited by John William Leonard.

(New York: Joseph & Sefton, 1922), 517

46 “E. Day Page Dies at Dinner Table”, The New York Times, December 26, 1918.

HISTORIC PRESERVATION PLAN

VAN ALLEN HOUSE PROPERTY

OAKLAND, BERGEN COUNTY, NEW JERSEY

2. DEVELOPMENTAL HISTORY

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

19

CONNOLLY & HICKEY HISTORICAL ARCHITECTS, LLC

in the Van Allen House. At the time the property was purchased by the Borough, the house was

tenanted by Oliver and Helen Lucia (Figure 26).

The Van Allen House was purchased by the Borough under threat of demolition for a gas station in

1966. A major advocate for the purchase was the former mayor Alexander Potash, who, as noted, lived in the house from 1938 to 1944. He recognized the property’s importance as one of the vanishing historical resources of Oakland seeing that the Borough was rapidly developing. The vision at the time was that the Vygeberg Office (Stream House) would serve as a local museum, presenting the Borough’s nineteenth-and-twentieth-century history, where the Van Allen House would represent the Colonial past of not only the Borough but the nation. The Oakland Historical Society, of which Mr. Potash was a founding member and the first president, has cared for the building since the purchase.

The stewardship of the Van Allen House and the Vygeberg Office (Stream House) has not been smooth. Conflicts between the Borough and the Historical Society as well as conflicts within the Historic Society itself began almost immediately. The Historical Society debated untiringly about the appropriate philosophy to guide restoration of the Van Allen Houses. Essentially they were conflicted between one of three philosophies: a purist approach that would return the building to its eighteenth-century appearance, a modern approach which would stabilize and restore the building as is, or an approach somewhere in-between in which the building would remain the current size and shape but some elements, such as dormers, would be removed in order to provide a more eighteenth-century appearance.

The early membership of the Historical Society leaned towards the purist approach and was such a strong advocate of it that Alexander Potash, an opponent, stepped down as President in protest in 1968. A document written in October 1973 by Roy Wright Jr., President, states that the goal of the Oakland Historical Society is to restore the building to 1777. However, the Society meeting minutes show that some of the membership was debating against the purist philosophy even at the time that document was written. In a newspaper article from spring of 1974, President Roy Wright Jr. explained that the original membership had a purist philosophy but under his leadership the Society has taken a more practical attitude. The prevailing philosophy over time appears to be one of keeping the building in its current layout but changing certain elements to provide an eighteenth-century appearance.

Regardless of the infighting, the early Oakland Historical Society was crucial in saving and caring for the Van Allen House (Figures 27 to 34). Since their early stewardship, they have researched the history, and pursued and received grants from historic preservation agencies. The early members of the Historical Society were occupied with clearing debris including removing animals and animal waste from the house, sandblasting the exterior masonry, and making critical repairs such as exterior painting, all accomplished through volunteers. They also began interior repairs such as removing the ceiling in the Parlor, repairing plaster and removing wallpaper in the Kitchen, removing the glass panels from the porch, and restoring the west second floor.

They recognized the importance of the building and the need for outside consultants with an expertise in historic buildings. As early as 1968, John Dickey, restoration architect, visited the site and provided a brief verbal assessment that the house was very important and should be restored to 1777. In 1973, John Boucher, Supervisor of Historic Sites of for the State of New Jersey, visited the house. He recommended several preservation architects including John Dickey. The Borough hired John Dickey to complete a Master Plan for the site based on the Society’s recommendations in 1976. The Plan was funded by grant money from the State.

HISTORIC PRESERVATION PLAN

VAN ALLEN HOUSE PROPERTY

OAKLAND, BERGEN COUNTY, NEW JERSEY

2. DEVELOPMENTAL HISTORY

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

20

CONNOLLY & HICKEY HISTORICAL ARCHITECTS, LLC

The Master Plan, completed in 1977, using the historic research completed by the Historical Society as a base, developed a construction chronology and made recommendations for the future restoration. The chronology will be addressed in Section 2.4 of this report. The Master Plan recommended an approach that fueled the controversy among the membership. The purists were unhappy because the report did not find enough evidence to develop a pure restoration while other members felt the approach was too aggressive and was creating a false sense of history that, regardless of philosophy, would be too expensive to achieve. The Borough hired Dickey to complete Phase I restoration drawings in June of 1977.

Refer to

Figures 27 to 34 and 37 to 47 for the condition before the 1979 restoration.

In the meantime, the Historical Society made a number of attempts to prove to the Borough that

Dickey’s approach was wrong. They hired another expert, Loring McMillan from Staten Island to assess the building. McMillan countered Dickey’s supposition about the chronology, and made

recommendations that essentially did not alter the exterior at all. Claire Tholl and Albin Roth, authors of the Survey of Dutch Stone Houses in Bergen County were also invited to the site to challenge Dickey’s philosophy. In a series of contentious correspondence between the Borough and the Historical Society between 1977 and 1978, the Historical Society thoroughly voiced their objections. Finally at the end of 1978, the bids for the Phase I Restoration as designed by Dickey were deemed much too expensive. The restoration was re-designed, having been significantly reduced in scope, and construction began in 1979.

Two members of the Oakland Historical Society served as the construction oversight as Dickey’s office was “unavailable for this task.” In the end, the Phase I Restoration created a more eighteenth-century appearance than the building had initially but was not a complete or necessarily accurate restoration. It included the removal of the entry porch, and construction of a new landing and steps, removal of the west exterior chimney, construction of a new interior chimney to vent the furnace, and removal of one chimney to below the roofline. It also included repointing the entire building including the chimneys, reroofing the main roof while removing the two south-facing dormers and repairing and painting all of the exterior wooden elements (Figures 48 to 50).

While the records are very incomplete from the 1980s and 1990s, two significant changes were recorded about the restoration of the Van Allen House. The first was the restoration of the cooking fireplace in the Kitchen, Room 104, (Figure 60) and the second was the repair of a significant structural deficiency in the Parlor, Room 102 (Figure 59).

The fireplace in the Kitchen had been removed prior to 1966. It appears that an enclosed stair to the

second floor was installed in its location. The wood panel walls protected the plaster finishes behind the stairs which included soot from the fireplace that apparently accurately outlined the firebox. The Dickey report contains a photograph of this area (Figure 44). Both Dickey and McMillan found evidence indicating a traditional English fireplace in this location. However, in 1984 when the drawings for the fireplace restoration were being completed, a Historical Society member objected to the English fireplace stating that this house would have had a jambless fireplace. The member, Stephan van Cline, who was also chairman of the Bergen County Historic Preservation Commission, quoted Claire Tholl and Ruth Van Wagoneer, of the Bergen County Office of Cultural and Historic Affairs, as stating that the fireplace should be jambless. The Society President, Chris Curran, and Vice President, Al John, argued that jambless fireplaces were only constructed in haste by settlers urgent to install fireplaces prior to winter, that they were often replaced by English fireplaces, and that such a fireplace would create a smoke and fire hazard if used. They noted eighteen other Dutch stone houses nearby that had English fireplaces.47

47 At least one of the houses mentioned in this list, the Doremus House in Towaco, has since removed the English fireplace and installed a jambless fireplace. The restoration was based on physical evidence.

HISTORIC PRESERVATION PLAN

VAN ALLEN HOUSE PROPERTY

OAKLAND, BERGEN COUNTY, NEW JERSEY

2. DEVELOPMENTAL HISTORY

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

21

CONNOLLY & HICKEY HISTORICAL ARCHITECTS, LLC

The English fireplace was installed and, unfortunately, any evidence of the original, if it remains, is

obscured by the modern construction. The second major repair was to remedy a substandard structural condition caused when the wall between the Borning Room and Parlor was removed to create one large room, Room 102, at the west end of the house. This occurred before the Borough acquired the building. A small beam (or top plate) remained supported by studs at either end to support the second floor framing above.

Michael Romanish, the borough building inspector, reported in 1975 that this beam was significantly undersized and that the structure below the studs in the basement was rotted and failing. The Historical Society designed the repair and repeatedly requested funding for this project. Finally in 1987, the funding was made available and the beam was replaced using a salvaged hand hewn member from another location.

Since 1987, other minor repairs and improvements have been made to the house but records of this work are incomplete.

2.1.3 The Vygeberg Office (Stream House)

As previously noted Edward Day Page purchased the Van Allen property in 1900 to be part of the

Vygeberg Estate and in 1902, constructed the Vygeberg Office (Stream House) where much of the farm business was conducted (Figure 18). The basement of the building served as the creamery for keeping dairy products according to long-time Oakland resident, Frank Scardo;48 there is evidence in the architecture to support this oral history. The water in the stream below the building helped to keep the dairy products cool and there are drain pipes in the floor to release the water that would was in the creamery process. The first floor served as the merchant floor where business was conducted and the second floor was a residence for tenants or workers.

After Page’s death in 1918, the first floor of the Vygeberg Office became the second location for the

Borough library. The Page estate changed hands in 1923 when his family sold the Van Allen property to a Catholic Seminary. The seminary allowed the library to remain in the Vygeberg building after taking ownership of the property, and it remained in that location until June 1932. While the first floor was used as a library, the second floor was tenanted. In 1931, the property was sold at a Sheriff’s auction to Edward M. Waldron Company, Incorporated. After the library moved, the first floor appears to have been divided and rented for additional living space.

Over the next thirty years, the Vygeberg Office changed hands with the Van Allen property several more times. In May 1932, Edward Waldron, Inc. conveyed the title to the Friar Tuck Club. In December 1932, the title was returned to Edward Waldron, Inc. A few later, Edward Waldron, Inc. conveyed the title to the National House & Farm Association in 1936. In 1950, the title was transferred to Mae Stern.

Prior to the transfer of title to Mae Stern, according to notes taken by the Oakland Historical Society, the first floor tenants were Mr. and Mrs. Harry Quick, and at the second floor was C. Montanya. In 1957, the property was purchased by Knoll Top Construction Corporation.

Concurrently as the restoration of the Van Allen House was causing tension between the Borough and the Historical Society, they were also debating the fate of the Vygeberg Office. In 1968, the Vygeberg Office was vandalized and the local building inspector wrote a report to the Borough requesting that the building be properly cleaned and then mothballed. The Historical Society felt this building would make an excellent museum and, in 1973, stated that the Vygeberg Office should be restored before the Van Allen House. The roof was repaired in 1974 but shortly afterwards vandals throwing stones damaged the

48 Karschner.

HISTORIC PRESERVATION PLAN

VAN ALLEN HOUSE PROPERTY

OAKLAND, BERGEN COUNTY, NEW JERSEY

2. DEVELOPMENTAL HISTORY

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

22

CONNOLLY & HICKEY HISTORICAL ARCHITECTS, LLC

new roof. A new heating system was being installed in 1975. However, at the same time as this work

was being completed, the building inspector made another assessment of the building and reported a

number of deficiencies to the Borough. In June of 1975, the Borough announced that they were giving control of the Vygeberg Office to the Bicentennial Committee. The Historical Society strongly objected stating that the Bicentennial Committee didn’t have the resources to repair the building. In September of 1975, the Oakland Historical Society wrote a letter demanding that the Borough stop wasting their money on the Vygeberg Office and concentrate on restoring the Van Allen House. In 1977, the building inspector again visited the site and found significant failures. The Borough hired a local architect, Fred Butler of Butler & Renes Architects, Montvale, NJ, to assess the building. The architect found it restorable but the building inspector countered the architect’s cost estimate, stating it wasn’t nearly high enough. It seems that the building then sat dormant for sometime afterward.

In 2001, the Oakland Historical Society began the Stream House Restoration Campaign. They undertook historic research,49 photographic documentation of existing conditions, and a nomination to the State and National Registers of Historic Places as an addendum to the Van Allen House nomination. The Oakland Historical Society solicited and received donations of building materials. It also removed the interior finishes and stored those they deemed original to the building in the basement for future re-installation.

Between 2002 and 2003, the Historical Society completed framing and subfloor repairs. Paint removal began but the difficulty in removing the paint created concern. The paint was tested for hazardous materials and was discovered to be composed of asbestos. As a result, paint removal efforts were halted.

The roofing tiles were removed at critical locations where roof framing required repair, but based on the building’s current appearances, the work was halted in the midst of construction.

Further work was undertaken in 2008. In 2002 the Oakland Historical Society received a $10,000 grant from the Bergen County Open Space, Recreation, Farmland and Historic Preservation Trust fund for the emergency stabilization of the Vygeberg Office. The work was completed in 2008 by Union Stone Cleaning and Restoration, Inc. based on recommendations made by Andrew F. Andersen, Inc., a structural engineering firm in Bernardsville, New Jersey.